The concept of closing the books refers to summarizing the information in the accounting records into the financial statements at the end of a reporting period.

Many steps are required to do so. In this article, we give an overview of closing journal entries and the most prevalent closing activities that an organization is likely to need.

The closing process does not begin after a reporting period has been completed. Instead, the bookkeeper should be preparing for it well in advance. By doing so, it is possible to complete a number of activities in a leisurely manner before the end of the month, leaving fewer items for the busier period immediately following the end of the period.

Accordingly, we have grouped the closing steps into the following categories:

1. Prior closing steps. These are the steps needed to complete the processing of the financial statements, and which can usually be completed before the end of the reporting period.

2. Core closing steps. These are the steps required for the creation of financial statements, and which cannot be completed prior to the end of the reporting period.

3. Delayed closing steps. These are the activities that can be safely delayed until after the issuance of the financial statements, but which are still part of the closing process.

The sections in this article do not necessarily represent

the exact sequence of activities that one should follow when closing the books;

the sequence should be based on the unique processes of an organization, and

the availability of employees to work on them.

Journal Entries

An important part of the closing process is the use of

journal entries to refine the reported financial results. In this section, we

discuss various aspects of journal entries – the accruals concept, adjusting

entries, reversing entries, and closing entries.

The Accruals Concept

An accrual allows you to record expenses and revenues for which you expect to expend cash or receive cash, respectively, in a future reporting period. The offset to an accrued expense is an accrued liability account, which appears in the balance sheet.

Check out this article to learn more about accruals.

The offset to accrued revenue is an accrued asset account (such as unbilled fees), which also appears in the balance sheet. Examples of accruals are:

- Revenue accrual. A company’s employees work billable hours on a project that will eventually invoice for $5,000. It can record an accrual in the current period so that its current income statement shows $5,000 of revenue, even though it has not yet billed the recipient.

- Expense accrual – interest. An organization has a loan with the local bank for $1 million and pays interest on the loan at a variable rate of interest. The invoice from the bank for $3,000 in interest expense does not arrive until the following month, so the business accrues the expense in order to show the amount on its income statement in the proper month.

- Expense accrual – wages. A company pays its employees at the end of each month for their hours worked through the 25th day of the month. To fully record the wage expense for the entire month, it also accrues $32,000 in additional wages, which represents the cost of wages for the remaining days of the month.

Most accruals are initially created as reversing entries so that the accounting software automatically cancels them in the following month. This happens when you are expecting revenue to actually be billed, or supplier invoices to actually arrive, in the next month. The concept is addressed later in the Reversing Entries sub-section.

Adjusting Entries

Adjusting entries are journal entries that are used at the end of an accounting period to adjust the balances in various general ledger accounts to more closely align the reported results and financial position of a business to meet the requirements of an accounting framework, such as the Singapore Financial Reporting Standards (SFRS).

An adjusting entry can be used for any type of accounting transaction; here are some of the more common ones:

- To record depreciation and amortization for the period

- To record an allowance for doubtful accounts

- To record accrued revenue

- To record accrued expenses

- To record previously paid but unused expenditures as prepaid expenses

- To adjust cash balances for any reconciling items noted in the bank reconciliation

Adjusting entries are most commonly of three types, which are:

- Accruals. To record a revenue or expense that has not yet been recorded through a standard accounting transaction.

- Deferrals. To defer a revenue or expense that has occurred, but which has not yet been earned or used.

- Estimates. To estimate the amount of a reserve, such as the allowance for doubtful accounts.

When a journal entry is recorded for an accrual, deferral,

or estimate, it usually impacts an asset or liability account. For example, if

you accrue an expense, this also increases a liability account. Or, if you

defer revenue recognition to a later period, this also increases a liability

account. Thus, adjusting entries impact the balance sheet, not just the income

statement.

Reversing Entries

When a journal entry is created, it may be to record revenue or an expense other than through a more traditional method, such as issuing an invoice to a customer or recording an invoice from a supplier. In these situations, the journal entry is only meant to be a stopgap measure, with the traditional recordation method still being used at a later date. This means that the bookkeeper has to eventually create a journal entry that is the opposite of the original entry, thereby cancelling out the original entry. The concept is best explained with an example.

EXAMPLE

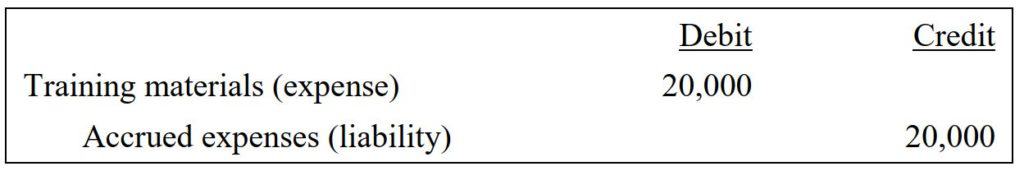

The bookkeeper of Archimedes Education has not yet received an invoice from a key supplier of training materials by the time he closes the books for the month of May. He expects that the invoice will be for $20,000, so he records the following accrual entry for the invoice:

This entry creates an additional expense of $20,000 for the month of May.

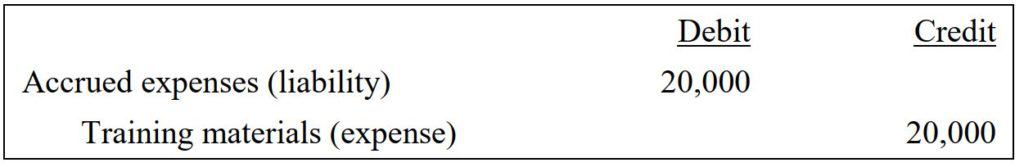

The bookkeeper knows that the invoice will arrive in June and will be recorded upon receipt. Therefore, he creates a reversing entry for the original accrual in early June that cancels out the original entry. The entry is:

The invoice then arrives and is recorded in the normal manner through the accounts payable module in Archimedes’ accounting software. This creates an expense during the month of June at $20,000. Thus, the net effect in June is:

In short, the accrual entry shifts recognition of the expense from June to May.

Any accounting software package contains an option for automatically creating a reversing journal entry when a journal entry is initially set up. Always use this feature when a reversing entry will be needed. By doing so, one can avoid the risk of forgetting to manually create the reversing entry, and also avoid the risk of creating an incorrect entry.

Tip: There will be situations where there is no expectation to

reverse a journal entry for a few months. If so, consider using an automated

reversing entry in the next month, and creating a replacement journal entry in

each successive month. While this approach may appear time-consuming, it

ensures that the original entry is always flushed from the books, thereby

avoiding the risk of carrying a journal entry past the date when it should have

been eliminated.

Common Adjusting Entries

This section contains a discussion of the journal entries that a business is most likely to need to close the books, along with an example of the accounts most likely to be used in the entries.

Depreciation

This entry is used to gradually charge the investment in fixed assets to expense over the useful lives of those assets. The amount of depreciation is calculated from a spreadsheet or fixed asset software, and is based on a systematic method for spreading recognition of the expense over multiple periods.

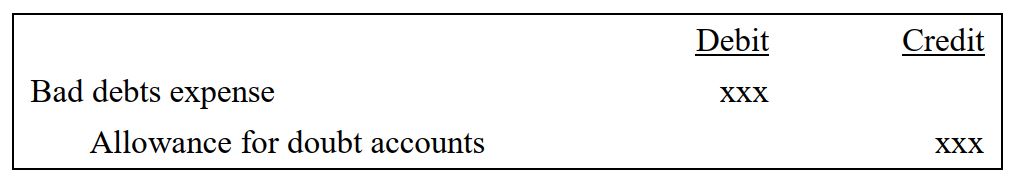

Allowance for Doubtful Accounts

If a business sells goods or services on credit, there is a strong likelihood that a portion of the resulting accounts receivable will eventually become bad debts. If so, update the allowance for doubtful accounts each month. This account is a contra asset account that offsets the balance in the accounts receivable account. Set the balance in this allowance to match the best estimate of how much of the month-end accounts receivable will eventually be written off as bad debts. A sample entry is:

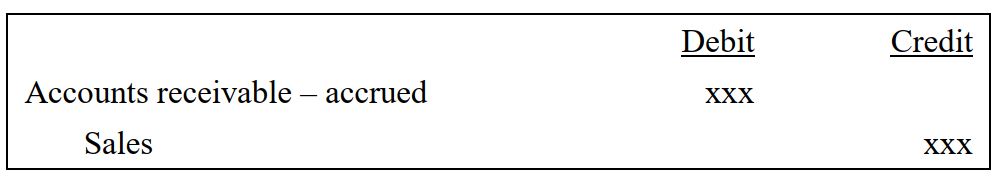

Accrued Revenue

If an organization has engaged in work for a customer but has not yet billed the customer, it may be possible to recognize some or all of the revenue associated with the work performed to date. The offset to the revenue is a debit to an accrued accounts receivable account. Do not record this accrual in the standard trade accounts receivable account, since that account should be reserved for actual billings. A sample of the accrued revenue entry is:

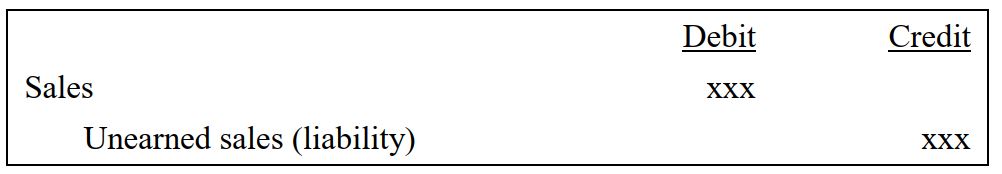

It is also possible for the reverse situation to arise, where a customer is invoiced in advance of completing work on the billed items. In this case, reduce recorded sales by the amount of unearned revenue by crediting an unearned sales (liability) account. A sample entry is:

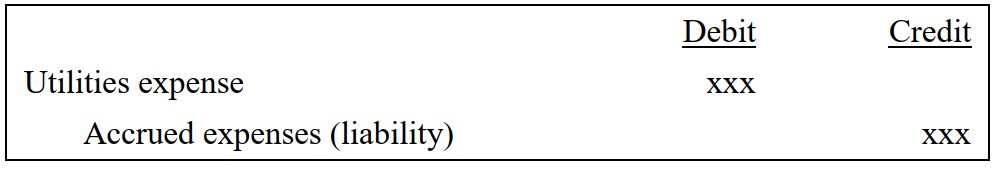

Accrued Expenses

If there are supplier invoices that you are aware of but have not yet received, estimate the amount of the expense and accrue it with a journal entry. There are any number of expense accounts to which such transactions might be charged; in the following sample entry, we assume that the expense relates to a supplier invoice for utilities that has not yet arrived.

This is likely to be the most frequent of the adjusting entries, as there may be a number of supplier invoices that do not arrive by the time an organization officially closes its books.

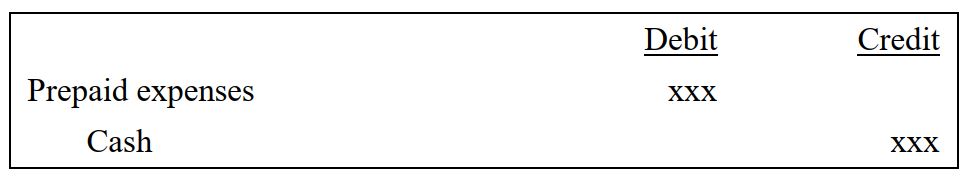

Prepaid Assets

Occasionally, an organization will make a significant payment in advance to a third party. This advance may be for something that will be charged to expense in a later period, or it may be a deposit that will be returned at a later date. These payments should initially be recorded as assets, usually in the prepaid assets account. Situations where one may record a prepaid asset include:

- Rent paid before the month to which it applies

- Insurance paid before the month to which it applies

- Rent deposit, to be returned at the conclusion of a lease

- Utilities deposit, to be retained until the organization cancels service

The name of the debited account can vary. We use “Prepaid

expenses” in the sample entry, but “Prepaid assets” is also used.

Closing Entries

Closing entries are journal entries used to flush out all temporary accounts at the end of an accounting period and transfer their balances into permanent accounts. Doing so resets the temporary accounts to begin accumulating new transactions in the next accounting period. A temporary account is an account used to hold balances during an accounting period for revenue, expense, gain, and loss transactions. These accounts are flushed into the retained earnings account at the end of an accounting period, leaving them with zero balances at the beginning of the next reporting year.

The basic sequence of closing entries is:

- Debit all revenue accounts and credit the income summary account, thereby clearing out the revenue accounts.

- Credit all expense accounts and debit the income summary account, thereby clearing out all expense accounts.

- Close the income summary account to the retained earnings account. If there was a profit in the period, this entry is a debit to the income summary account and a credit to the retained earnings account. If there was a loss in the period, this entry is a credit to the income summary account and a debit to the retained earnings account.

The result of these activities is to move the net profit or loss for the period into the retained earnings account, which appears in the balance sheet.

Since the income summary account is only a transitional

account, it is also acceptable to close directly to the retained earnings

account and bypass the income summary account entirely.

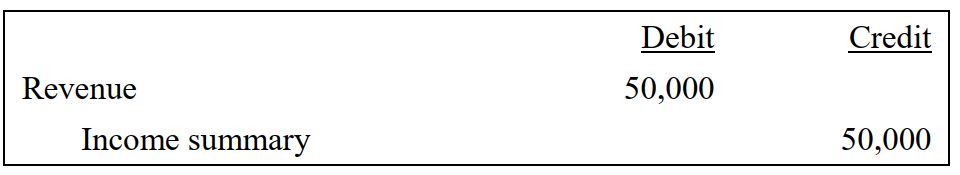

EXAMPLE

Archimedes Education is closing its books for the most recent accounting period. Archimedes had $50,000 of revenues and $45,000 of expenses during the period. For simplicity, we assume that all of the expenses were recorded in a single account; in a normal environment, there might be dozens of expense accounts to clear out. The sequence of entries is:

1. Empty the revenue account by debiting it for $50,000, and transfer the balance to the income summary account with a credit. The entry is:

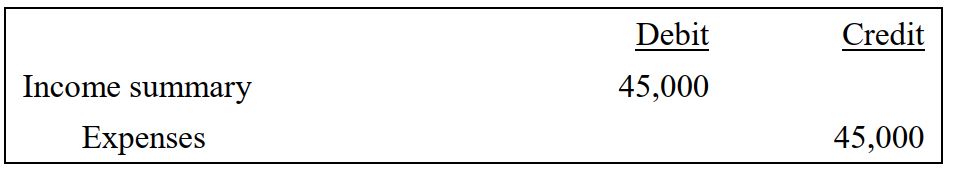

2. Empty the expense account by crediting it for $45,000, and transfer the balance to the income summary account with a debit. The entry is:

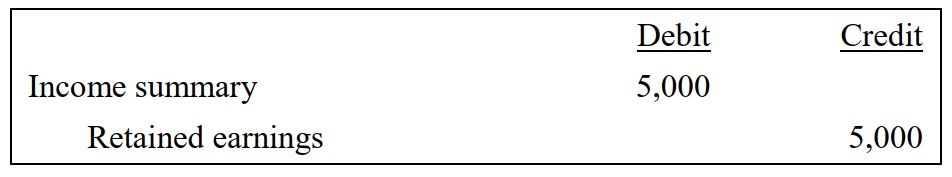

3. Empty the income summary account by debiting it for $5,000, and transfer the balance to the retained earnings account with a credit. The entry is:

These entries have emptied the revenue, expense, and income summary accounts, and shifted the net profit for the period to the retained earnings account.

We should point out that a practising bookkeeper rarely uses these closing entries since they are handled automatically by any accounting software package. Instead, the basic closing step is to access an option in the software to close the accounting period. Doing so automatically populates the retained earnings account and prevents any further transactions from being recorded in the system for the period that has been closed.

Prior Closing Steps: Update Reserves

If an organization is using the accrual basis of accounting, create a reserve in the expectation that expenses will be incurred in the future that are related to revenues generated now. This concept is called the matching principle. Under the matching principle, record the cause and effect of a business transaction at the same time.

Thus, when revenue is recorded, also record within the same accounting period any expenses directly related to that revenue. An example of this type of expense is the allowance for doubtful accounts; this allowance is used to charge to expense the amount of bad debts that are expected from a certain amount of sales before you know precisely which items will not be paid.

There is no need to create a reserve if the balance in the account is going to be immaterial. Instead, many businesses can generate perfectly adequate financial statements that only have a few reserves, while charging all other expenditures to expense as incurred.

Core Closing Steps: Create Customer Invoices

Part of the closing process may include the issuance of month-end invoices to customers. Irrespective of the number of invoices to be issued, invoices are always an important part of the closing process, because they are the primary method for recognizing revenue. Consequently, a significant part of the closing process is normally spent verifying that all possible invoices have, in fact, been created.

If some revenues are considered to not yet be billable, but to have been fully earned by the organization, accrue the revenue with a journal entry. This is common in construction industries where companies bill based on completion of milestones. Whereas the management can choose to recognize revenue on an input method first.

The accounting software should have an accounts receivable module that is used to enter customer invoices. This module automatically populates the accounts receivable account in the general ledger when invoices are created. Thus, at month-end, one can print the aged accounts receivable report and have the grand total on it match the ending balance in the accounts receivable general ledger account. This means that there are no reconciling items between the aged accounts receivable report and the general ledger account.

If there is a difference between the two numbers, it is almost certainly caused by the use of a journal entry that debited or credited the accounts receivable account. The bookkeeper should never create such a journal entry, because there is so much detail in the accounts receivable account that it is very time-consuming to wade through it to ascertain the source of the variance.

The primary transaction that the bookkeeper will be tempted to record in the accounts receivable account is accrued revenue. Instead, create a current asset account called “Accrued Revenue Receivable” and enter the accruals in that account. By doing so, normal accounts receivable transactions are segregated from special month-end accrual transactions.

Core Closing Steps: Reconcile the Bank Statement

Closing cash is all about the bank reconciliation because it matches the amount of cash recorded by the organization to what its bank has recorded. Once a bank reconciliation has been constructed, you can have considerable confidence that the amount of cash appearing on the statement of financial position is correct.

At a minimum, conduct a bank reconciliation shortly after the end of each month, when the bank sends a bank statement containing the bank’s beginning cash balance, transactions during the month, and its ending cash balance. It is even better to conduct a bank reconciliation every day based on the bank’s month-to-date information, which should be accessible via online banking. By completing a daily bank reconciliation, problems can be spotted and corrected immediately.

Core Closing Steps: Calculate Depreciation

Once all fixed assets have been recorded in the accounting

records for the month, calculate the amount of depreciation (for tangible

assets) and amortization (for intangible assets). This is a significant issue

when there is a large investment in fixed assets, but may be so insignificant in

other situations that it is sufficient to only record depreciation at the end

of the year.

Core Closing Steps: Accounts Payable

Accounts payable can be a significant bottleneck in the closing process. The reason is that some suppliers only issue invoices at the end of each month when they are closing their books, so the organization will not receive their invoices until several days into the next month. This circumstance usually arises either when a supplier ships something near the end of the month or when it is providing a continuing service. There are several choices for dealing with these items:

- Do nothing. If you wait a few days, the invoices will arrive in the mail, and you can record the invoices and close the books. The advantage of this approach is a high degree of precision and perfect supporting evidence for all expenses. It is probably the best approach at year-end, if the intent is to have the financial statements audited. The downside is that it can significantly delay the issuance of financial statements.

- Accrue continuing service items. As just noted, suppliers providing continuing services are more likely to issue invoices at month-end. When services are being provided on a continuing basis, you can easily estimate what the expense should be, based on prior invoices. Thus, it is not difficult to create reversing journal entries for these items at the end of the month. It is likely that these accruals will vary somewhat from the amounts on the actual invoices, but the differences should be immaterial.

- Accrue based on purchase orders. As just noted, suppliers issue invoices at month-end when they ship goods near that date. If the business is using purchase orders to order these items, the supplier is supposed to issue an invoice containing the same price stated on the purchase order. Therefore, if an item is received at the receiving dock but there is no accompanying invoice, use the purchase order to create a reversing journal entry that accrues the expense associated with the received item.

In short, we strongly recommend using accruals to record expenses for supplier invoices that have not yet arrived. The sole exception is the end of the fiscal year, when the outside auditors may expect a greater degree of precision and supporting evidence, and will expect the bookkeeper to wait for actual invoices to arrive before closing the books.

The accounting software should have an accounts payable module that is used to enter supplier invoices. This module automatically populates the accounts payable account in the general ledger with transactions. Thus, at the end of the month, one can print the aged accounts payable report and have the grand total on that report match the ending balance in the accounts payable general ledger account; there are no reconciling items between the aged accounts payable report and the general ledger.

If there is a difference between the two numbers, it is almost certainly caused by the use of a journal entry that debited or credited the accounts payable account. Such a journal entry should never be created because there is so much detail in the accounts payable account that it is very time-consuming to wade through it to ascertain the source of the variance.

The one transaction that the bookkeeper will be tempted to record in the accounts payable account is the accrued expense. Instead, create a current liability account in the general ledger called “Accrued Expenses” and enter the accruals in that account. By doing so, normal accounts payable transactions are being properly segregated from special month-end accrual transactions.

This differentiation is not a minor one. Accrual transactions require more maintenance than standard accounts payable transactions, because they may linger through multiple accounting periods, and you need to monitor them to know when to eliminate them from the general ledger. This problem can be addressed with reversing journal entries, but some accruals may not be designated as reversing entries, which calls for long-term tracking. If one were to lump accrued expenses into the accounts payable account, it would be very difficult to continually monitor the outstanding accruals.

In summary, restrict the accounts payable account to standard payables transactions, which makes it extremely easy to reconcile at month-end. Any transactions related to accounts payable but which are entered via journal entries should be recorded in a separate account.

Core Closing Steps: Review Journal Entries

It is entirely possible that some journal entries were made incorrectly, in duplicate, or not at all. Print the list of standard journal entries and compare it to the actual entries made in the general ledger, just to ensure that they were entered in the general ledger correctly. Another test is to have someone review the detailed calculations supporting each journal entry, and trace them through to the actual entries in the general ledger. This second approach takes more time, but is useful for ensuring that all necessary journal entries have been made correctly.

If there is an interest in closing the books quickly, the

latter approach could interfere with the speed of the close; if so, authorize

this detailed review at a later date, when someone can conduct the review under

less time pressure. However, any errors found can only be corrected in the following

accounting period, since the financial statements will already have been

issued.

Core Closing Steps: Reconcile Accounts

It is important to examine the contents of the balance sheet accounts to verify that the recorded assets and liabilities are supposed to be there. It is quite possible that some items are still listed in an account that should have been flushed out a long time ago, which can be quite embarrassing if they are still on record when the auditors review the company’s books at the end of the year. Here are several situations that a proper account reconciliation would have caught:

- Prepaid assets. An organization pays $10,000 to an insurance company as an advance on its regular monthly medical insurance, and records the payment as a prepaid asset. The asset lingers on the books until year-end, when the auditors inquire about it, and the full amount is then charged to expense.

- Accrued revenue. An entity accrues revenue of $50,000 for a services contract, but forgets to reverse the entry in the following month, when it invoices the full $50,000 to the client. This results in the double recordation of revenue, which is not spotted until year-end. The bookkeeper then reverses the accrual, thereby unexpectedly reducing revenues for the full year by $50,000.

- Depreciation. A business calculates the depreciation on several hundred assets with an electronic spreadsheet, which unfortunately does not track when to stop depreciating assets. A year-end review finds that the organization charged $40,000 of excess depreciation to expense.

- Accumulated depreciation. An entity has been disposing of its assets for years, but has never bothered to eliminate the associated accumulated depreciation from its balance sheet. Doing so reduces both the fixed asset and accumulated depreciation accounts by 50%.

- Accounts payable. An organization does not compare its accounts payable detail report to the general ledger account balance, which is $8,000 lower than the detail. The auditors spot the error and require a correcting entry at year-end, so that the account balance matches the detail report.

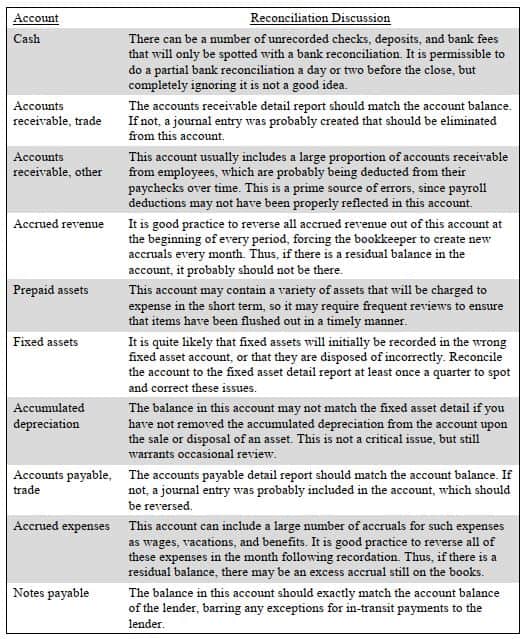

These issues and many more are common problems encountered at year-end. To prevent the extensive error corrections caused by these problems, conduct account reconciliations every month for the larger accounts, and occasionally review the detail for the smaller accounts, too. The following are some of the account reconciliations to conduct, as well as the specific issues to look for:

Sample Account Reconciliation List

The number of accounts that can be reconciled makes it clear

that this is one of the larger steps involved in closing the books. Selected

reconciliations can be skipped from time to time, but doing so presents the

risk of an error creeping into the financial statements and not being spotted

for quite a few months. Consequently, there is a significant risk of issuing

inaccurate financial statements if some reconciliations are continually

avoided.

Core Closing Steps: Close Subsidiary Ledgers

Depending on the type of accounting software used, it may be necessary to resolve any open issues in subsidiary ledgers, create a transaction to shift the totals in these balances to the general ledger (called posting), and then close the accounting periods within the subsidiary ledgers and open the next accounting period. This is most likely to involve ledgers for inventory, accounts receivable, and purchases.

Other accounting software systems (typically those developed more recently) do not have subsidiary ledgers, or at least use ones that do not require posting, and so are essentially invisible from the perspective of closing the books.

Core Closing Steps: Create Financial Statements

When all of the preceding steps have been completed, print the financial statements, which include the following items:

- Income statement

- Balance sheet

- Statement of cash flows

- XBRL formatting

If the financial statements are only to be distributed internally, it may be acceptable to only issue the income statement and balance sheet, and dispense with the other items just noted. Reporting to people outside of the organization generally calls for the issuance of the complete set of financial statements, including disclosures.

Core Closing Steps: Review Financial Statements

Once all of the preceding steps have been completed, review the financial statements for errors. There are several ways to do so, including:

- Horizontal analysis. Print reports that show the income statement, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows for the past twelve months on a rolling basis. Track across each line item to see if there are any unusual declines or spikes in comparison to the results of prior periods, and investigate those items. This is the best review technique.

- Budget versus actual. Print an income statement that shows budgeted versus actual results, and investigate any larger variances. This is a less effective review technique, because it assumes that the budget is realistic, and also because a budget is not usually available for the balance sheet or statement of cash flows.

There will almost always be problems with the first

iteration of the financial statements. Expect to investigate and correct

several items before issuing a satisfactory set of financials. To reduce the

amount of time needed to review financial statement errors during the core

closing period, consider doing so a few days prior to month-end; this may

uncover a few errors, leaving a smaller number to investigate later on.

Core Closing Steps: Accrue Tax Liabilities

Once the financial statements have been created and the information in them has been finalized, there may be a need to accrue an income tax liability based on the amount of net profit. There are several issues to consider when creating this accrual:

• Income tax rate. When accruing income taxes, use the average income tax rate that you expect to experience for the full year after accounting for tax deductions.

• Losses. If the entity has earned a taxable profit in a prior period of the year and has now generated a loss, accrue for a tax rebate, which will offset the tax expense that was paid in the prior year. This is known as Loss Carry-Back Relief. You can read more about it here.

Once the income tax liability has been accrued, print the

complete set of financial statements.

Core Closing Steps: Close the Month

Once all transactions have been entered into the accounting

system, close the month in the accounting software. This means prohibiting any

further transactions in the general ledger in the old accounting period, as

well as allowing the next accounting period to accept transactions. These steps

are important, so that you do not inadvertently enter transactions into the

wrong accounting periods.

Core Closing Steps: Add Disclosures

If the organization is issuing financial statements to readers other than the management team, do add disclosures to the basic set of financial statements. There are many disclosures required under SFRS. It is especially important to include a complete set of disclosures if the financial statements are being audited. If so, the auditors will offer advice regarding which disclosures to include.

Allocate a large amount of time to the proper construction

and error-checking of disclosures, for they contain a number of references to

the financial statements and subsets of financial information extracted from

the statements, and this information could be wrong. Thus, every time a new

iteration of the financial statements is created, the disclosures should be

updated.

Core Steps: Issue Financial Statements

The final core step in closing the books is to issue the financial statements. There are several ways to do this. If there is an interest in reducing the total time required for someone to receive the financial statements, convert the entire package to PDF documents and e-mail them to the recipients. Doing so eliminates the mail float that would otherwise be required. If a number of reports are being incorporated into the financial statement package, this may require the purchase of a document scanner.

When issuing financial statements, always print a copy and

store it in a binder. This gives ready access to the report during the next few

days, when managers from around the organization are most likely to contact the

bookkeeper with questions about it.

Summary

This article has outlined a large number of steps that are needed to close the books. The level of organization required to close the books in this manner might appear to be overkill. However, consider that one of the most visible work products of the bookkeeper is the financial statements. If you can establish a reputation for consistently issuing high-quality financial statements within a reasonable period of time, this will likely be the basis for the organization’s view of the entire department.

Need help with closing your books? Contact us now for a free 30-min consultation call.