Where is accounting information stored? The central database

for accounting transactions is the ledger. The primary storage area is the

general ledger, but information can be fed into the general ledger from

subsidiary ledgers too, in situations where a large amount of information must

be stored. To understand how information storage works in the accounting area,

we will delve into the concept of the ledger, describe several types of

ledgers, and then proceed to a summary of the information in the general

ledger, which is called a trial balance.

The Ledger Concept

A ledger is a book or database in which double-entry accounting transactions are stored or summarized. A subsidiary ledger is a ledger designed for the storage of specific types of accounting transactions.

If a subsidiary ledger is used, the information in it is then summarized and posted to an account in the general ledger, which in turn is used to construct the financial statements of a company.

The account in the general ledger where this summarized information is stored is called a control account. Most accounts in the general ledger are not control accounts; instead, transactions are recorded directly into them.

A subsidiary ledger can be set up to offload data storage for virtually any general ledger account. However, they are usually only created for areas in which there are high transaction volumes, which limits their use to a few areas. Examples of subsidiary ledgers are:

• Accounts receivable ledger

• Fixed assets ledger

• Inventory ledger

• Purchases ledger

Tip: Subsidiary ledgers are used when there is a large amount of transaction information that would clutter up the general ledger. This situation typically arises in companies with significant sales volume. Thus, there may be no need for subsidiary ledgers in a small company.

As an example of the information in a subsidiary ledger, the inventory ledger may contain transactions pertaining to receipts into stock, movements of stock to the production floor, conversions into finished goods, scrap and rework reporting, and sales of goods to customers.

In order to research accounting information when a subsidiary ledger is used, drill down from the general ledger to the appropriate subsidiary ledger, where the detailed information is stored. Consequently, if there is a preference to conduct as much research as possible within the general ledger, use fewer subsidiary ledgers.

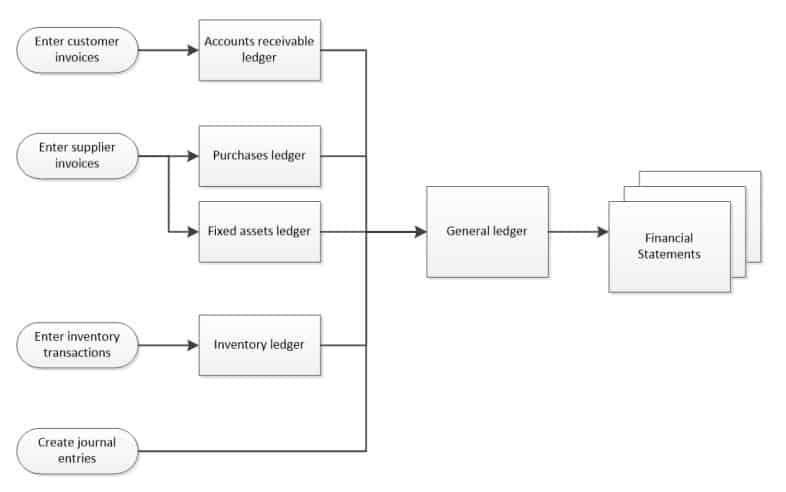

The following chart shows how the various data entry modules

within an accounting system are used to create transactions which are recorded

in either the general ledger or various subsidiary ledgers, and which are

eventually aggregated to create the financial statements.

Transaction Flow in the Accounting System

Part of the period-end closing process is to post the information in a subsidiary ledger to the general ledger. This is usually a manual step, so verify that all subsidiary ledgers have been appropriately completed and closed before posting their summarized totals to the general ledger. It can be quite a problem if you forget to post the totals from a subsidiary ledger to the general ledger, since that means the resulting financial statements may be missing a batch of crucial transactions.

Tip: If subsidiary ledgers are used, include a step in the

closing procedure to post the balances in all subsidiary ledgers to the general

ledger, as well as to verify that the subsidiary ledgers have been closed and

shifted forward to the next accounting period.

Posting to the General Ledger

Posting refers to the aggregation of financial transactions from where they are stored in subsidiary ledgers, and transferring this information into the general ledger. Information in one of the subsidiary ledgers is aggregated at regular intervals, at which point a summary-level entry is made and posted in the general ledger. In a manual bookkeeping environment, the aggregation may occur at fixed intervals, such as once a day or once a month. For example, if the source ledger were the accounts receivables ledger, the aggregated posting entry might include a debit to the accounts receivable account, and credits to the sales account and various sales tax liability accounts. When posting this entry in the general ledger, a notation could be made in the description field, stating the date range to which the entry applies.

In a computerized bookkeeping environment, posting to the general ledger may be unnoticeable. The software simply does so at regular intervals, or asks if you want to post, and then handles the underlying general ledger posting automatically.

It is possible that no posting transaction even appears in

the reports generated by the system. Posting to the general ledger does not

occur for lower-volume transactions, which are already recorded in the general

ledger. For example, fixed asset purchases may be so infrequent that there is

no need for a subsidiary ledger to house these transactions, so they are

instead recorded directly in the general ledger.

General Ledger Overview

A general ledger is the master set of accounts in which is summarized all transactions occurring within a business during a specific period of time. The general ledger contains all of the accounts currently being used in a chart of accounts, and is sorted by account number. Either individual transactions or summary-level postings from subsidiary ledgers are listed within each account number, and are sorted by transaction date. Each entry in the general ledger includes a reference number that states the source of the information. The source may be a subsidiary ledger, a journal entry, or a transaction entered directly into the general ledger.

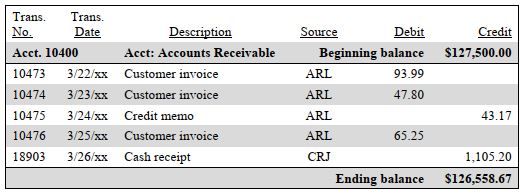

The format of the general ledger varies somewhat, depending on the accounting software being used, but the basic set of information presented for an account within the general ledger is:

- Transaction number. The software assigns a unique number to each transaction, so that it can be more easily located in the accounting database if the transaction number is known.

- Transaction date. This is the date on which the transaction was entered into the accounting database.

- Description. This is a brief description that summarizes the reason for the entry.

- Source. Information may be forwarded to the general ledger from a variety of sources, so the report should state the source, in case there is a need to go back to the source to research the reason for the entry.

- Debit and credit. States the amount debited or credited to the account for a specific transaction.

The following sample of a general ledger report shows a possible format that could be used to present information for several transactions that are aggregated under a specific account number.

Sample General Ledger

It is extremely easy to locate information pertinent to an accounting inquiry in the general ledger, which makes it the primary source of accounting information. For example:

- A manager reviews the balance sheet and notices that the amount of debt appears too high. The bookkeeper looks up the debt account in the general ledger and sees that a loan was added at the end of the month.

- A manager reviews the income statement and sees that the bad debt expense for his division is very high. The bookkeeper looks up the expense in the general ledger, drills down to the source journal entry, and sees that a new bad debt projection was the cause of the increase in bad debt expense.

As the examples show, the source of an inquiry is frequently the financial statements; when conducting an investigation, the bookkeeper begins with the general ledger, and may drill down to source documents from there to ascertain the reason(s) for an issue.

We will now proceed to brief discussions of the accounts

receivable ledger and purchase ledger, which are representative of the types of

subsidiary ledgers that can be used to compile information within the

accounting system.

The Accounts Receivable Ledger

The accounts receivable ledger is a subsidiary ledger in which is recorded all credit sales made by a business. It is useful for segregating into one location a record of all amounts invoiced to customers, as well as all credit notes issued to them, and all payments made against invoices by them. The ending balance of the accounts receivable ledger equals the aggregate amount of unpaid accounts receivable.

A typical transaction entered into the accounts receivable ledger will record an account receivable, followed at a later date by a payment transaction from a customer that eliminates the account receivable.

If a manual record of the accounts receivable ledger were to be maintained, it could contain substantially more information than is allowed by an accounting software package. The data fields in a manually-prepared ledger might include the following information for each transaction:

- Invoice date

- Invoice number

- Customer name

- Identifying code for item sold

- GST tax invoiced

- Total amount billed

- Payment flag (states whether paid or not)

- Salesperson (for commission calculation)

The primary document recorded in the accounts receivable ledger is the customer invoice. Also, if a credit is granted to a customer for such items as returned goods or items damaged in transit, a credit note may be recorded in the ledger. Alternatively, a sales return ledger may be created.

The information in the accounts receivable ledger is aggregated periodically and posted to a control account in the general ledger. This account is used to keep from cluttering up the general ledger with the massive amount of information that is typically stored in the accounts receivable ledger. Immediately after posting, the balance in the control account should match the balance in the accounts receivable ledger. Since no detailed transactions are stored in the control account, anyone wanting to research customer invoice and credit memo transactions will have to drill down from the control account to the accounts receivable ledger to find them.

Before closing the books and generating financial statements

at the end of an accounting period, all entries must be completed in the

accounts receivable ledger, after which the ledger is closed for that period,

and totals posted from the accounts receivable ledger to the general ledger.

The Purchase Ledger

The purchase ledger is a subsidiary ledger in which is recorded all purchases made by a business. It is useful for segregating into one location a record of the amounts the company is spending with its suppliers. The purchase ledger shows which purchases have been paid for and which ones remain outstanding. A typical transaction entered into the purchase ledger will record an account payable, followed at a later date by a payment transaction that eliminates the payable.

Thus, there is likely to be an outstanding account payable balance in the ledger at any time. If a manual record of the purchase ledger were to be maintained, it could contain substantially more information than is allowed by an accounting software package.

The data fields in a manually-prepared purchase ledger might include the following information for each transaction:

- Purchase date

- Supplier code (or name)

- Supplier invoice number

- Purchase order number (if used)

- Identifying code for item purchased

- Amount paid

- Sales tax paid

- Payment status (states whether paid or not)

- Purchaser

The primary document recorded in the purchase ledger is the supplier invoice. Also, if suppliers grant a credit back to the business for such items as returned goods or items damaged in transit, credit note issued by suppliers would be recorded in the purchase ledger.

The information in the purchase ledger is aggregated periodically and posted to a control account in the general ledger. The purchase ledger control account is used to keep from cluttering up the general ledger with the massive amount of information that is typically stored in the purchase ledger. Immediately after posting, the balance in the control account should match the balance in the purchase ledger.

Since no detailed transactions are stored in the control account, anyone wanting to research purchase transactions will have to drill down from the control account to the purchase ledger to find them.

Before closing the books and generating financial statements

at the end of an accounting period, all entries must be completed in the

purchase ledger, after which the ledger is closed for that period, and totals

posted from the purchase ledger to the general ledger.

Reconciling the General Ledger

When a person is reconciling the general ledger, this usually means that individual accounts within the general ledger are being reviewed to ensure that the source documents match the balances shown in each account.

The reconciliation process at the account level typically includes the following steps:

- Beginning balance investigation. Match the beginning balance in the account to the ending reconciliation detail from the prior period. If the amounts do not match, investigate the reason for the variance in the prior period. If the account has not been reconciled for some time, it is possible that the error lies several periods in the past.

- Current period investigation. Match the transactions reported in the account within the period to the underlying transactions, and adjust as necessary.

- Adjustments review. Review all adjusting journal entries recorded in the account within the period for appropriateness, and adjust as necessary.

- Reversals review. Ensure that all journal entries that should have reversed within the period have been reversed.

- Ending balance review. Verify that the ending detail for the account matches the ending account balance.

Overview of the Trial Balance

The trial balance is a report run at the end of an accounting period. It is primarily used to ensure that the total of all debits equals the total of all credits, which means that there are no unbalanced journal entries in the accounting system that would make it impossible to generate accurate financial statements.

Printing the trial balance to match debit and credit totals has fallen into disuse since accounting software rejects the entry of unbalanced journal entries.

The trial balance can also be used to manually compile financial statements, though, with the predominant use of computerized accounting systems that create the statements automatically, the report is rarely used for this purpose.

When the trial balance is first printed, it is called the

unadjusted trial balance. Then, when the bookkeeper corrects any errors found

and makes adjustments to bring the financial statements into compliance with

the accounting standards, the report is called the adjusted trial balance.

Finally, after the period has been closed, the report is called the

post-closing trial balance.

The Trial Balance Format

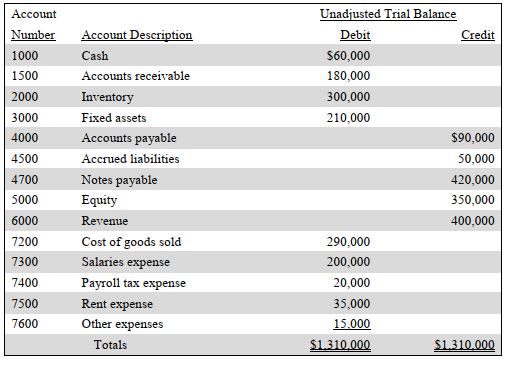

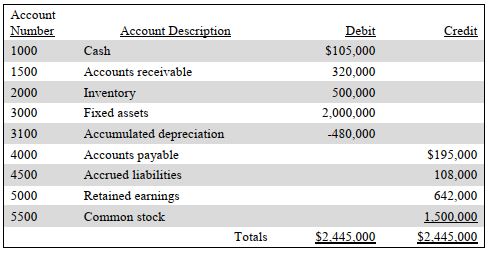

The initial trial balance report contains the following columns of information:

- Account number

- Account name

- Ending debit balance (if any)

- Ending credit balance (if any)

Each line item only contains the ending balance in an account, which comes from the general ledger. All accounts having an ending balance are listed in the trial balance; usually, the accounting software automatically blocks all accounts having a zero balance from appearing in the report, which reduces its length. A sample trial balance follows.

Sample Trial Balance

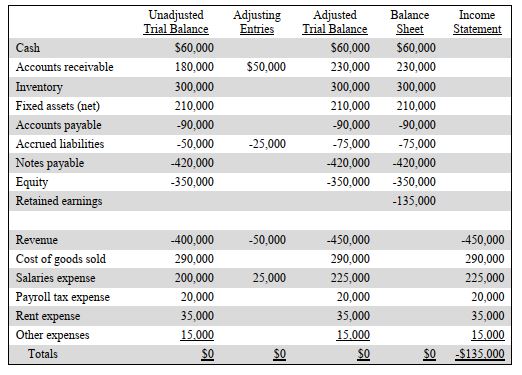

The Extended Trial Balance

An extended trial balance is a standard trial balance to which are added categories extending to the right, and in which are listed the account totals for the balance sheet and the income statement. Thus, all asset, liability, and equity accounts are stated in a balance sheet column, and all revenue, expense, gain, and loss accounts are stated in an income statement column.

The extended trial balance is useful for creating a visual representation of where each of the accounts in the standard trial balance goes in the financial statements, and may be useful for detecting anomalies in the trial balance that should be corrected (as discussed further in the next section).

A sample of an extended trial balance is shown below. It uses the same trial balance information used to describe the adjusted trial balance format.

Sample Extended Trial Balance

Any computerized accounting system automatically generates financial statements from the trial balance, so the extended trial balance is not a commonly generated report in computerized systems.

Note: The information in the balance sheet and income

statement columns in an extended trial balance do not necessarily match the

final presentation of these reports, because some of the line items may be

aggregated for presentation purposes.

Trial Balance Error Correction

There may be a number of errors in the trial balance, only a few of which are easy to identify. Here are some suggestions on how to find these problems:

- Entries made twice. If a journal entry or other transaction is made twice, the trial balance will still be in balance, so this is not a good report for finding duplicate entries. Instead, it may be necessary to wait for the issue to resolve itself. For example, a duplicate invoice to a customer will be rejected by the customer, while a duplicate invoice from a supplier will (hopefully) be spotted during the invoice approval process.

- Entries not made at all. This issue is impossible to find on the trial balance, since it is not there. The best alternative is to maintain a checklist of standard entries, and verify that all of them have been made.

- Entries to the wrong account. This may be apparent with a quick glance at the trial balance, since an account that previously had no balance at all now has one. Otherwise, the best form of correction is preventive – use standard journal entry templates for all recurring entries.

- Reversed entries. An entry for a debit may be mistakenly recorded as a credit, and vice versa. This issue may be visible on the trial balance, especially if the entry is large enough to change the sign of an ending balance to the reverse of its usual sign.

- Unbalanced entries. This issue is listed last, since it is impossible in a computerized environment where entries must be balanced or the system will not accept them. If a manual system is being used, the issue will be apparent in the column totals of the trial balance. However, locating the exact entry causing the problem is vastly more difficult, and will call for a detailed review of every entry, or at least the totals in every subsidiary ledger that rolls into the general ledger.

Whenever an error is corrected, be sure to use a clearly

labeled journal entry with supporting documentation, so that someone else can

verify the work at a later date. After reviewing the error correction issues in

this section, you may have noticed how poor a role the trial balance plays in

the detection of errors. In fact, it is nearly impossible to detect an error

solely through this report. Instead, it is necessary to use other, more

detailed reports to determine the real cause of an error.

The Post-Closing Trial Balance

A post-closing trial balance is a listing of all balance sheet accounts containing balances at the end of a reporting period. The post-closing trial balance contains no revenue, expense, or summary account balances, since these temporary accounts have all been closed and their balances moved into the retained earnings account in the balance sheet. A temporary account is an account used to hold balances during an accounting period for revenue, expense, gain, and loss transactions. These accounts are flushed into the retained earnings account at the end of an accounting period.

The post-closing trial balance contains columns for the account number, account description, debit balance, and credit balance. In most accounting systems, this report does not have a different report title than the usual trial balance.

The post-closing trial balance is used to verify that the total of all debit balances equals the total of all credit balances, which should net to zero. Once you have ensured that this is the case, begin recording accounting transactions for the next accounting period.

A sample post-closing trial balance is shown in the following sample. Notice that there is no column for adjusting entries, and that there are no temporary accounts, such as revenue and expense accounts.

Sample Post-Closing Trial Balance

Evaluation of the Trial Balance

We have described the layout of the trial balance and how it can be used – but is it really needed? The answer depends upon whether a business is using a computerized accounting system or a manual one. In a computerized environment, the system automatically generates financial statements, literally at the touch of a button.

In this situation, there is no particular need for a trial balance. The user of a computerized accounting system is more likely to go directly to the general ledger to review the details for each account than to first print out a trial balance to see where a problem might lie, and then go to the general ledger to spot the problem. In short, a computerized system renders the trial balance unnecessary.

The situation is quite a bit different for the user of a manual accounting system. In this case, one would shift the account balances in the general ledger to the trial balance, and then manually create the financial statements from that information. In essence, the extended trial balance noted in an earlier section becomes the primary tool for constructing financial statements.

The only case in which the user of a computerized accounting system might find it necessary to print a trial balance is when the external auditors request a copy of it.

Summary

The bookkeeper will likely spend a great deal of time dealing with the general ledger since it is the ultimate source of accounting information. You will find that it is not overly efficient to switch back and forth between the subsidiary ledgers and the general ledger when engaged in any research.

Consequently, we recommend that the number of subsidiary ledgers is kept to a minimum so that as many transactions as possible are available within the general ledger. This also reduces the risk that the balance in a subsidiary ledger will not be posted forward into the general ledger, resulting in inaccurate financial statements.

The trial balance is essentially a summary of the account balances for businesses as of a point in time. It was heavily used in an era when financial statements were generated by hand but have since fallen out of use as computerized systems have taken over the production of financial statements.

Nonetheless, we include it here both to provide a historical perspective on how information is summarized, and also because it is still used for the manual creation of financial statements. At a minimum, it is likely to remain on the list of standard computerized accounting reports, so the bookkeeper should be familiar with the information on it, and how this information is used.